Review: LA Times by Christopher Knight, We Are Here / Here We Are

It’s my honor to be included this thoughtful and sprawling review of Durden and Ray’s show”We Are Here / Here We Are”, by LA Times’ Prize-winning art writer, Christopher Knight. Congratulations to Durden and Ray’s Sean Noyce, co-curators Arezoo Bharthania, Jennifer Celio, Joe Davidson, Dani Dodge, Roni Feldman, Jenny Hager, Curtis Stage, Valerie Wilcox, Steven Wolkoff, Alison Woods, and all the other incredible participating artists!

http://www.durdenandray.com/participating-artists

Review: Miss seeing art? 100 artists come to the rescue with work in public view across L.A.

By CHRISTOPHER KNIGHT ART CRITIC

MAY 22, 2020

6 AM

Abel Alejandre’s “Street Fighter” is displayed on a Signal Hill fence. The gallery Durden and Ray has enlisted 100 artists to place their work in public around Los Angeles County. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Time

A chain-link fence around an urban oil field is an unlikely display space to show a work of art. In Signal Hill, however, that’s exactly the location Abel Alejandre chose for “Street Fighter,” his punchy black and white print.

Alejandre is one of 100 artists participating in the sprawling, shrewdly conceived show “We Are Here / Here We Are” organized by the artist-run Durden and Ray gallery in downtown Los Angeles. Small, tightly focused shows have been the gallery’s specialty, but the unprecedented modern pandemic brought on by the novel coronavirus has sent it in a different direction.

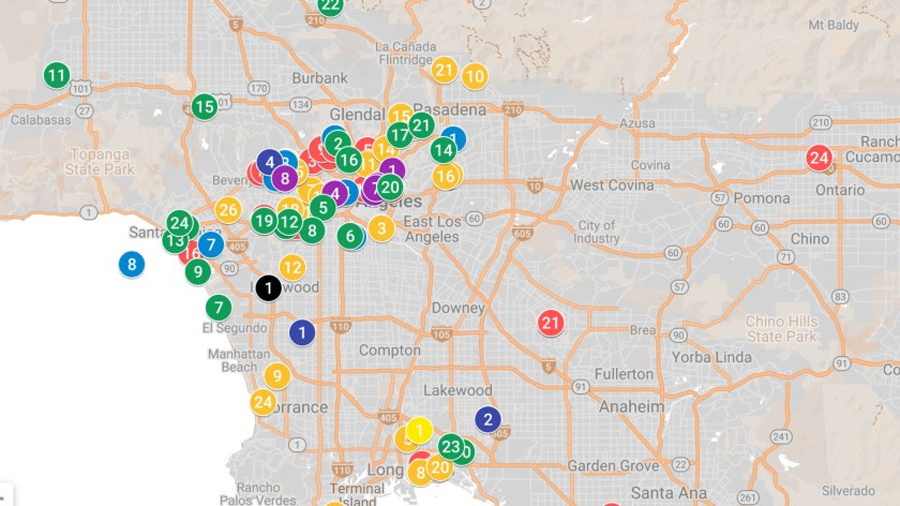

Ninety-seven works have been installed all over Los Angeles County in places viewable from the street or sidewalk. Unlike other such art exhibitions — a small but growing phenomenon, since most museums and galleries closed and the migration of art to online digital platforms has proved less than satisfying — this one is not concentrated in a particular part of the city. Instead, it embraces L.A. sprawl.

Sites include a bus bench, a home’s front yard, the roll-up door on a unit in an industrial park, a gym’s front window, a home’s overgrown backyard, the entry to an abandoned parking garage and scores more. Among them is that Signal Hill fence.

“Street Fighter” is a sign, not unlike a yard sign produced during an election year. What appears to be a woodcut or linocut print is affixed to an 11-by-17-inch sheet of cardboard and attached to a wood stake.

It fits in as the fourth in a lineup with three campaign signs left over from the recent March elections. Alejandre’s wordless image shows a sinewy man, his raised fists propelled by an explosion of white that frames his body.

The location resonates. A dreary stretch of conventional roadway between an oil field, derricks pumping away in the distance, and a pair of fast-food restaurants flanking a big-box hardware store creates a working milieu for street signs imploring votes for candidates for local judgeships.

Alejandre’s street fighter is a kind of veiled self-portrait. The artist inserts himself as a creative, nonviolent combatant in the public effort for justice.

Alejandre was born in a small town in Michoacán, Mexico. His affecting print, smartly injected into the flow of daily life, takes its place in the famous tradition of the Taller de Gráfica Popular — the People’s Print Workshop, a sociopolitical project that once flourished in Mexico City.

“What Now?” – a photo collage in Woodland Hills by Constance Mallinson – is created with plastic litter and photos of endangered species and environments. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

In Woodland Hills, 45 miles north of Signal Hill, a second chain-link fence displays a very different artwork. At an overgrown backyard in a leafy suburban neighborhood, Constance Mallinson has crafted an assemblage sculpture.

“What Now?” is composed of ordinary plastic refuse scavenged from area streets. A lunch bowl, bottle, cup, several lids, a broken toy — each bit of litter is decorated with a photo-collage that shows an animal, person or place suffering from the ravages of petroleum- and natural gas-derived plastics.

Colorful National Geographic-style images include a swimming turtle, pink coral polyps, a woman and child fording floodwaters, and a green frog. A white polar bear leaps from an ice floe in a picture affixed to a white plastic foam tray. Unseen consequences embedded in the production and distribution of plastics, a ubiquitous bit of industrial manufacture, are brought into poignant view.

Mallinson’s astute choice of an overgrown patch of suburbia cordoned off by a chain-link fence renders the photographic subjects as casually disposable as the plastic litter. Not only does “What Now?” gain quiet authority by not hectoring, it also acquires a sense of generosity: The artist included a typed sheet to explain the exhibition, adding that a viewer is welcome to unfasten and take home any of the photo-collage pieces.

So the assemblage might be gone when you go, not unlike a disappearing coral reef or Arctic bear.

Chris Trueman’s “DPW” is displayed on a roll-up door in an Upland industrial park.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Mark Steven Greenfield’s totem sculpture, “Homage to Mestra Didi,” stands in the garden of an Altadena home. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Messing with the art is of course a risk for any public exhibition like this. (Nine works disappeared within days of the May 16 opening.) Sixty miles east, at the rear of a small industrial park in Upland, Chris Trueman has bolted a large painting to a roll-up door of one unit.

Paintings aren’t usually hung outdoors and exposed to the elements. The only other person around on the day I saw it was the diligent operator of a parking lot sweeper. The experience was oddly thrilling.

Partly that’s because, at a time when galleries and museums are shuttered and one mostly stays at home, rarity suddenly describes seeing in person all but a few types of art, like video and digital images. This is the first painting I’ve laid eyes on in months, outside my own house.

I wouldn’t push the analogy too far, but for a moment it made me think what it must have been like to see painted pictures before 1839. That’s when the camera’s invention opened the door to mechanical reproduction, releasing what became a flood of analog and then digital pictures that we now experience daily. Imagery lost its miraculous quality as a simple given.

And partly the pleasure came from Trueman’s sly evocation of Gerhard Richter, the celebrated German artist whose paintings of the past 50 years have addressed the image torrent and its perceptual complications. Trueman’s abstract painting, titled “DPW” (inescapably suggesting Department of Public Works) is a layered, graffiti-like composition of gestural marks and spray paint, mostly in green, yellow and gray, plus black and white.

Atmospheric optical space opens up, despite being painted on a polypropylene support. Color sits on the surface because the synthetic material can’t absorb acrylic paint. Pigment puddles, streaks and clouds.

The direct, expressive immediacy of the artist’s hand is undercut, replaced by a strangely photoshopped appearance — a painting at once present yet one step removed. The person-size picture looks distinctly worn, not unlike the ordinary metal door on which it hangs.

More than 100 miles separate these three works. (Talk about social distancing.) “We Are Here / Here We Are” is not a show that will likely by seen in its entirety by many people. Instead it has a neighborly feel.

Ismael de Anda III’s “The Sun Came Out Last Night and Sang to Me” is on display in the windows of a San Marino gym. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Adam Francis Scott and Julie Whaley’s translucent painting “Corita, Constance, Richard, and Sharon (A Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose)” greets visitors to a 1955 Richard Neutra-designed house. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

That’s one of its charms. This is art offered to folks out walking the dog, bicycling in the neighborhood or otherwise going about their business. (It continues through June 20, dawn to dusk.)

It’s also easy enough to see a number of pieces by making an itinerary through a somewhat concentrated area. In all there are (or were) 28 sculptures, 27 installations, 26 paintings and drawings and 16 photographs, videos, prints and collages.

At a house in Altadena, Mark Steven Greenfield has installed a totem-like sculpture in the lovely front-yard garden. A tall cone of graduated, multicolored plastic vessels, big pot at the bottom and small drinking glass at the top, is animated by swirling plastic ties. The vessel structure is an “Homage to Mestre Didi,” the shamanistic Afro-Brazilian who believed that memory is art’s catalyst.

A few minutes away by car, Kim Abeles fashioned a slipcover for a bus bench at the northeast corner of East Washington Boulevard and North Hill Avenue. Her homemade textile, photo-printed with an image of a bed of pine cones and pine needles, is an amenity for mass transportation that, ideally, might help restore the natural world being intimately pictured.

Or, at least, it was an amenity. The work vanished within a day.

A bus bench slipcover by artist Kim Abeles disappeared within a day of being installed. (Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Two big photographs by Ismael de Anda III in the windows of a small, shuttered San Marino gym show fantastic satellites spinning through outer space. Look closely, and the sci-fi spaceships are assembled from photo-collage fragments of farm equipment, a down-to-earth memory of the artist’s West Texas childhood transformed into heady aspirations for the future. Welcome to L.A.

Up a winding road in the Pasadena hills, Adam Francis Scott and Julie Whaley have installed a big, translucent scrim painted in pink and purple shapes. Greeting visitors at the front door to the modest post-and-beam house, built in 1955 by the celebrated architect Richard Neutra, the work unfolds as a circular chain reaction of art.

The painting derives from a 1968 Sister Corita silkscreen print, “A Rose Is a Rose,” once owned by art historian Constance Perkins, for whom Neutra designed the house. The clipped “rose” quotation from Gertrude Stein asserts the simultaneity of individual and interconnected identity. The California-raised poet’s century-old avant-garde milieu winds through midcentury efforts by Perkins, Neutra and Corita to reach Scott and Whaley working in the new millennium.

Rebecca Niederlander’s sculpture in Eagle Rock, “Central Sensitization,” is made of wood slats bolted together. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Labkhand Olfatmanesh’s “Cycle (Baby Maybe)” ties water-filled bags, one holding a baby doll, to a Sherman Oaks tree. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Down the hill, in nearby Eagle Rock, another house and its front garden, designed in a compact Japanese style, are the pedestal for a curling, coiling, looping sculpture made from wooden strips visibly bolted together. Rebecca Niederlander’s elegant “Central Sensitization” climbs a tall tree by a dry stream composed from rocks, then leaps to the car port like an ambitious wisteria.

The title refers to a condition in the central nervous system that produces chronic pain — an ailment that might describe our current COVID-19-riddled society — while the sculpture’s form is an artful diagram of that bodily system. Two doors up, a spectacular magenta bougainvillea unexpectedly repeats Niederlander’s form on another house, climbing to the roof in a visual rhyme that layers pain with everyday pleasure.

That’s one of the most appealing features of “We Are Here / Here We Are.” The serendipity of art encounters in public places is embedded in ordinary experience. Going into art museums and galleries is certainly gratifying, but these works thrive beyond institutions or the marketplace.

Certainly, some works can be taxing. Next to the driveway into an abandoned parking garage on a Sherman Oaks side street, Labkhand Olfatmanesh translates a conundrum about natural and social pressures that women encounter. Her installation features a dozen fluid-filled plastic bags, all tied up in a tree with yards of twine.

A bag at the top, just out of reach, holds a baby doll, while another at the base is empty, flattened and held down on the ground by a rock. Within the installation’s plain reference to a tree of life, a subtle intimation of violence echoes in the context of abstention from elevated motherhood. The tree, unsurprisingly, is an evergreen.

The handy map at the Durden and Ray website (durdenandray.com) will get you to the expansive exhibition’s far-flung sites. (Missing works are being removed from the map.) Beyond that useful function, though, the map also gives graphic, edifying heft to a simple reality: Artists are everywhere in the L.A. sprawl, living and working among us. Good to know, especially in tough times.

The map to the Durden and Ray exhibition spans L.A. County. (Durden and Ray Gallery)

https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2020-05-22/durden-ray-we-are-here-art-show-public

Additional Press for this project:

http://www.durdenandray.com/project-press